When I first stepped into the field of machine learning, I spent quite a large amount of time on reading papers and trying to implement them. Of course, I was no genius and by implementing I meant git clone and trying to run the authors’ code. For concepts that interests me, I’d also type out the code and annotate them to get a better understanding. I imagine many others to have the similar journey when starting out.

The journey is not all rosy but a frustrating one. The story of trying to reproduce a paper usually starts like this — A state-of-the-art (SOTA) paper strikes headline in popular newsfeeds (twitter) and creates buzz. You then dig into the paper and skim through in quick time. Next, you are impressed by the seemingly good result presented in a slick table format and you want to lay your hands on it.

What follows is the frantic search for code and trying to run it on the same dataset reported by the authors. Right now, you crossed your fingers and hope that the stars are aligned: the instruction to run (README.md), the code, the parameters, the dataset, the path pointing to the dataset, the software environment, the required dependencies and the hardware you have, so that you can reproduce the SOTA results.

At this junction, you may find a few common problems (listed below). Of course, these are not exhaustive and I hope you can spot these signs before investing your time on it. After all, no one likes going down the rabbit hole and coming out empty handed.

Common Problems when Reproducing a Machine Learning Paper

- Incomplete or missing README

- Undeclared dependencies, buggy code and missing pre-trained model

- Undisclosed parameters

- Private dataset or missing pre-processing steps

- Unrealistic requirement for GPU resource

Incomplete or missing README

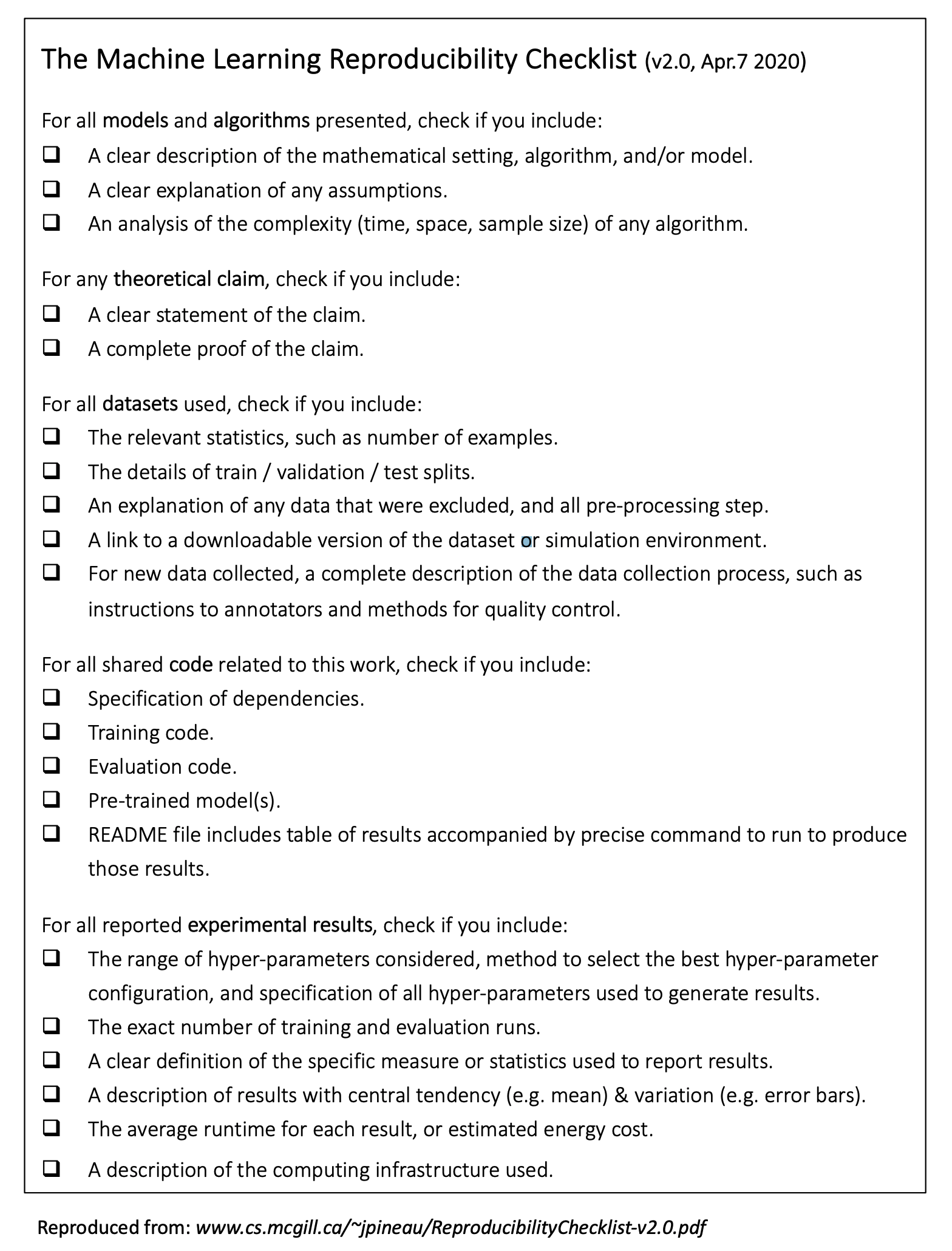

If a paper is published with code, then the README is one of the documentation you’d start with. A good README typically consist of several components such as the listing of dependencies, training scripts, evaluation scripts, pretrained models and its results from running the scripts. In fact these are listed in the ML Code Completeness Checklist by Papers with Code and is now part of the official NeurIPS 2020 code submission process! See the sample README here. This checklist is originally inspired by Joelle Pineau, a faculty member at Mila and an Associate Professor at McGill University, and it serves as a good guideline when striving for reproducibility. Incomplete README would definitely suggest a bad start in running the code.

One specific sign to watch out for is the presence of sample notebooks or sample code. These notebooks are helpful for starters to hit the ground running by demonstrating the use of code. Ideally you should be able to run these notebooks without modifying anything except for hitting “Run all”. Command lines pre-populated with parameters and data paths should also serve the same purpose. e.g. python run.py -data /path/to/data -param 0.5 -output /path/to/model/output

Some other minor but helpful information such as the authors’ contact details, diagrams or gif ( 😍) that illustrate model architecture or data transformation process are also signs of a well documented README. If the code repository is hosted on Github, check if the questions under Issues are actively answered or if pull requests are regularly reviewed. These are signs that the repository is actively maintained and ensure that you have a good support network moving forward. Of course there are exceptions; just be careful if one or more of those mentioned here are missing.

Joelle Pineau’s Machine Learning Reproducibility Check list - (https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~jpineau/ReproducibilityChecklist.pdf)

Undeclared dependencies, buggy code and missing pre-trained model

After you are satisfied with the sample notebooks, you might be tempted to try the model with your own dataset using different parameters. At this stage you may make function calls that are not used in the sample notebooks or decide to try out the pre-trained model on your dataset. This is where you are likely to encounter roadblocks.

For example, you may notice that the requirements.txt are not present or that the package version are not pinned (e.g. tensorflow==2.2). Just imagine the horror when you find out that TensorFlow is using version 1.15 instead of 2.2 just because the version is not specified by the authors.

Granted that you have the dependencies checked, but now you notice that the trained model mentioned is missing! With that, you could either 1) debug the code 2) file a bug report or 3) ignore the code. Be careful with option 1 as you may end up wasting hours on it. Of course there are bugs that are easy to solve and usually I will submit a pull request if I manage to fix it. But since not every day is Sunday so these low hanging fruits can be hard to come by.

Missing pre-trained model can be a red flag but it is not something uncommon. Ultimately, the authors are not obligated to release them. So an alternative is to train the model using the stated parameters and spend GPU-hours to (re)produce one. Did I mention that the parameters are not always declared? Let’s move on to the next point.

Undisclosed parameters

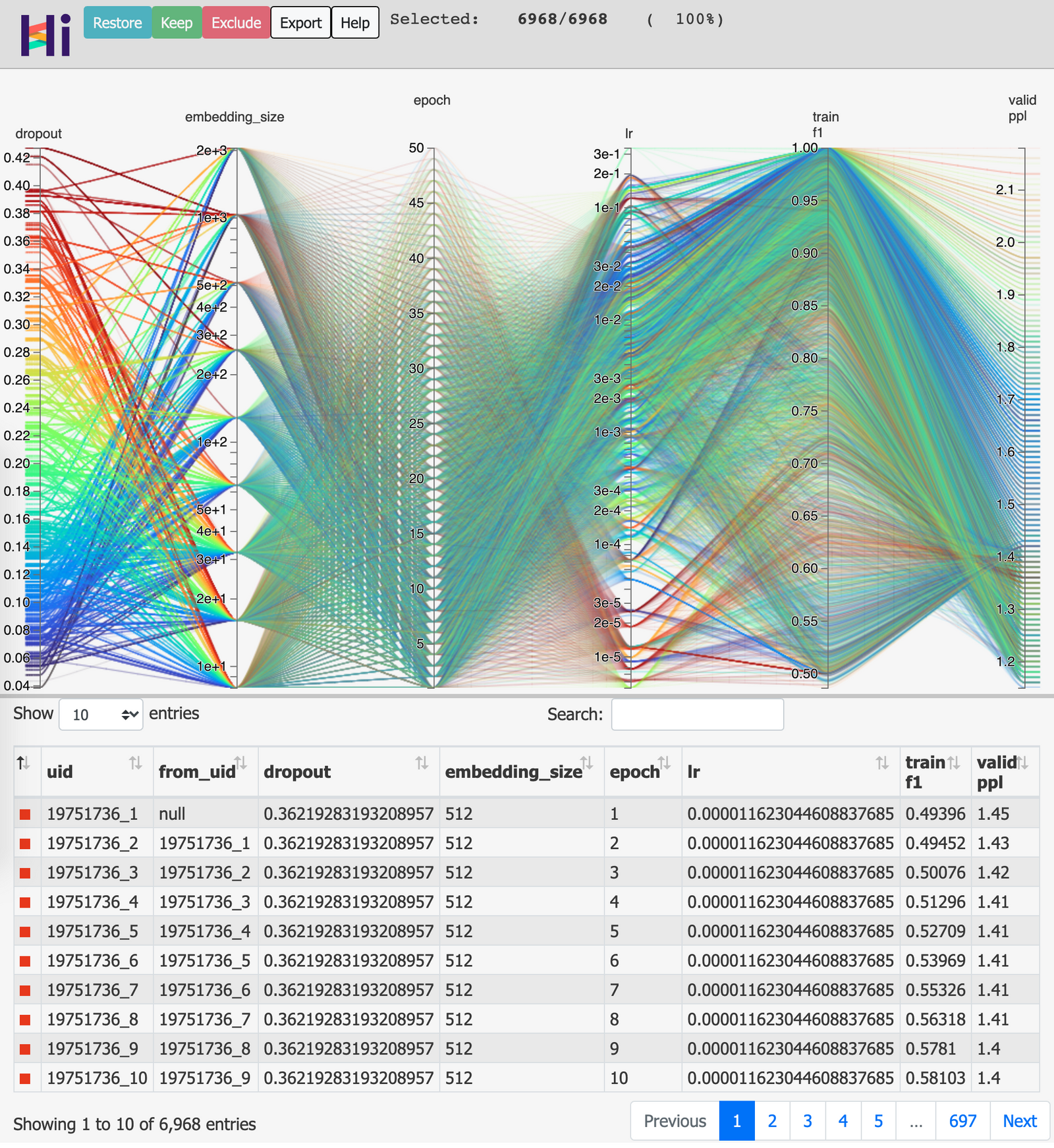

Depending on the model, hyper-parameters can be super important in achieving SOTA results. From the screenshot below, you can see that different parameters produce different f1 scores (ranging from 0.5 to 1.0). The ingredients (parameters) that goes into a model are typically learning rates, embedding size, number of layers, amount of dropout, batch size, number of epochs trained for and many more. The parallel plot below (HiPlot by Facebook) is a good tool to help you visualise the model result when using different combinations of parameters.

So if the authors did not provide the exact parameters they use, you may have to go through all the experiments yourself to reproduce the SOTA results — just count the number of lines below!

Parallel Plot to visualise high dimensional data - HiPlot by Facebook

Private dataset or missing pre-processing steps

In many ways, we are lucky to have open-source datasets contributed by researchers around the world. Let’s face it — data collection is never easy. The same goes for cleaning these data and formatting them for public use. I am grateful to the academics and kaggle for hosting these open-source datasets free-of-charge. The bandwidth and storage cost must be insane.

However, for repositories using private dataset, it is not always easy to get hold of them — especially when the datasets may contain copyrighted information e.g imagenet. Typically you will need to fill up a request form and the copyright holder will approve at their discretion.

This process can be a hassle at times and if you do not have the required dataset handy, you might want to think twice before moving forward. Or… you can search and download it from alternate sources… like this one.

Unrealistic requirement for GPU resource

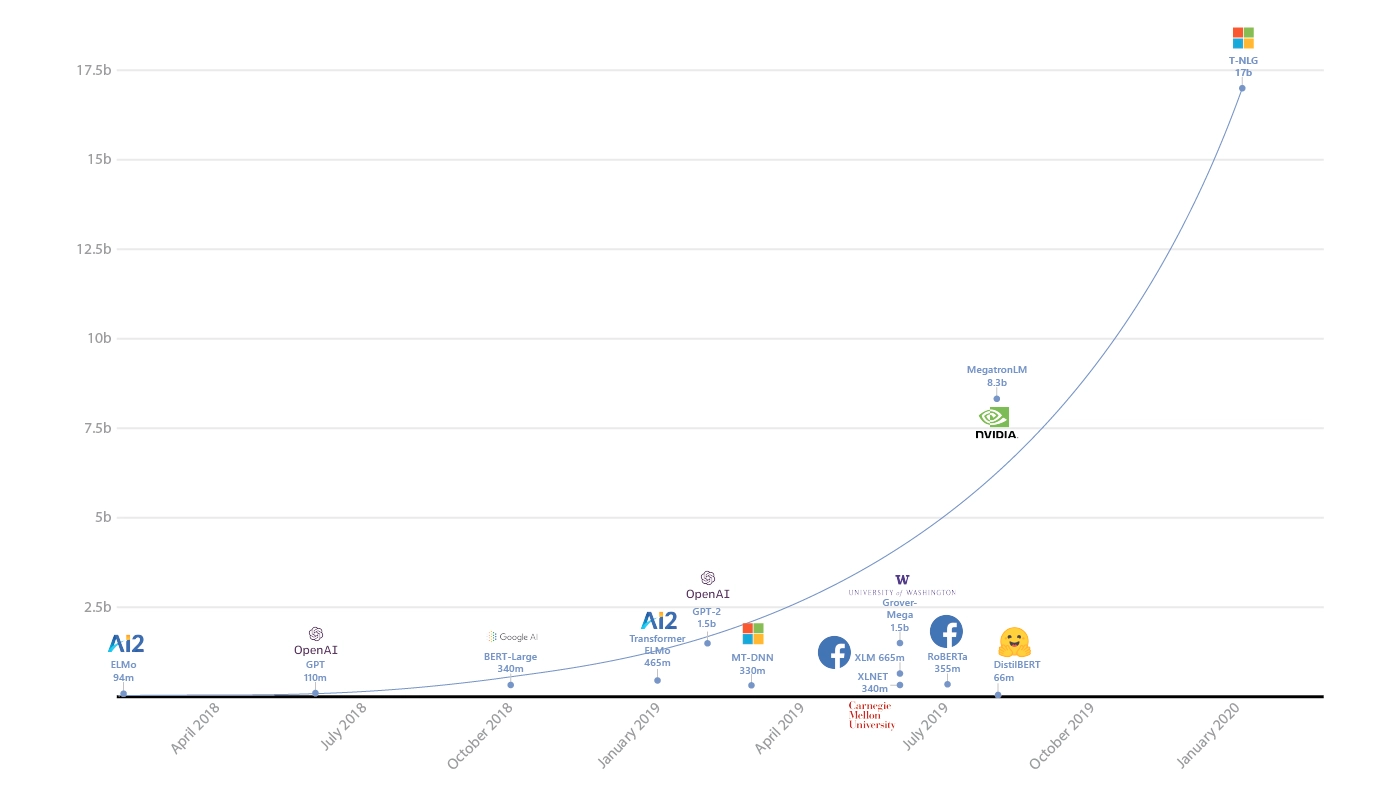

Recently there is a trend where larger models lead to better performance. This means that there are cases where SOTA papers are produced require the compute power of a whole data center. These papers are certainly not easy to reproduce. For example, Google released a paper in Oct 2019 in attempt to explore the limits of Transformer model architecture by pushing the number of parameters to 11 billions, only to find themselves beaten by Microsoft with Turning-NLG using 17 billions parameters few months later.

To train model with billions of parameters definitely require a distributed way of model training coupled with some form of high performance compute (HPC) or GPU clusters. To illustrate, models with 11B and 17B of parameters would take up approximately 44GB and 68GB of ram respectively, so there is no way these model can fit into just 1 GPU (at least not in 2020).

In short, it always helps to find out early if the paper is using extra large model that is beyond your capacity.

Microsoft trains world’s largest Transformer language model. No, it will not work with your desktop GPU https://venturebeat.com/2020/02/10/microsoft-trains-worlds-largest-transformer-language-model/

Summary

Reproducing a paper with code is not easy but we are beginning to see more projects trying to standardised the consumption of SOTA models for all to enjoy. My personal favourite is HuggingFace’s Transformers where it offers super low barriers to entry for researchers and practitioners. We also saw the uprising of TensorFlow’s Model Garden and PyTorch’s Model Zoo where pre-trained models are built by the same team behind popular deep learning frameworks.

These repositories aim to standardise the usage of pre-trained models and provide a go-to place for model contribution and distribution. They provide assurance to code quality and tend to have good documentation. I hope the community can benefit from these super-repositories and help us reproduce SOTA results and consume SOTA models with ease.

References

- Why Can’t I Reproduce Their Results (http://theorangeduck.com/page/reproduce-their-results)

- Rules of Machine Learning: Best Practices for ML Engineering (https://developers.google.com/machine-learning/guides/rules-of-ml)

- Curated list of awesome READMEs (https://github.com/matiassingers/awesome-readme)

- How the AI community can get serious about reproducibility (https://ai.facebook.com/blog/how-the-ai-community-can-get-serious-about-reproducibility/)

- ML Code Completeness Checklist (https://medium.com/paperswithcode/ml-code-completeness-checklist-e9127b168501)

- Designing the Reproducibility Program for NeurIPS 2020 (https://medium.com/@NeurIPSConf/designing-the-reproducibility-program-for-neurips-2020-7fcccaa5c6ad)

- Tips for Publishing Research Code (https://github.com/paperswithcode/releasing-research-code)